Amnesty

"Now as a veteran against the war, I gravitated to the issue of amnesty for Vietnam war resisters, no doubt because emotionally I sympathized deeply with their plight and their decision in contrast to my own course."

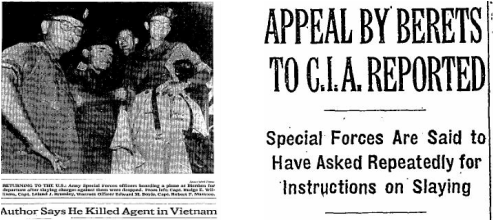

Newspaper clippings after assassination of CIA agent by green berets in Vietnam, Oct. and Aug. 1969

In my last year in the Army when I was stationed in Pearl Harbor, I began a novel, probably as an exercise to rid myself of the demons I felt as a soldier at the height of the Vietnam War. The protagonist was a young Army intelligence officer who sends an unwitting agent deep into Communist China on a mission, only to see his agent caught and executed. The book was full of the angst and moral confusion of my generation. After my discharge I returned to Chapel Hill to work on the book, and when it was finished, began to experience the pain of rejection that many first novelists know. But in August of 1969 a story appeared in the New York Times about the “termination” of an untrustworthy Vietnamese agent who was working with the Green Berets. The CIA was denying responsibility, and from my experience, I knew that was a lie. So I wrote an angry letter to the Times about it, and then piled in my battered VW bug and drove to New York, to see an editor at Viking who had, gently but encouragingly, rejected the novel. When a week later I arrived back at my dirt road in NC and fished out the mail from my mailbox, there was a telegram from an Evan Thomas at a company called W.W. Norton. It read:

“Any chance of a book to follow your most interesting letter in the Times?”

When an author screams in the woods far out of earshot, does he make a sound?

I did not know what W.W. Norton was, or who Evan Thomas was, but I quickly learned that Norton was a distinguished independent publishing house, and Thomas was the son of the famous socialist of the 1930s, Norman Thomas. In his own right, Evan was a legendary NY editor who had edited William Manchester’s famous book on the JFK assassination. He quickly became my editor, and W.W. Norton published To Defend, To Destroy in the spring of 1971. As the world turns, I was hired to teach creative writing at UNC that fall, a job I held for the next ten years.

"Herndon's story in Reston's sympathetic hands cuts into the very tissue of the national debate and merits wide reading."

- Publisher's Weekly on The Amnesty of John David Herndon

I had turned passionately against the Vietnam War. Nixon came into office, promising to end the war quickly and kept it going until he was driven from office five years later, at the cost of another 20,000 American lives. Now as a veteran against the war, I gravitated to the issue of amnesty for Vietnam war resisters, no doubt because emotionally I sympathized deeply with their plight and their decision in contrast to my own course. For the next seven years, as an advocate for universal amnesty, I wrote more than any American writer about the issue. In 1970 my first magazine piece treated the Nuremburg parallel and was published in the Saturday Review. I began to debate the issue all over America, often pitted against snarling, patronizing right wing commentators. And in 1973 I published my first non-fiction book, The Amnesty of John David Herndon.

It was the story of a deserter, living in exile in Paris, who agreed to become the first test case on amnesty, by returning to America to face the music. Inevitably, the military wished to avoid a show trial and cashiered Herndon out of the service administratively and quietly. We were denied the stage we sought.

My obsession with amnesty did not end until President Jimmy Carter proclaimed a pardon for Vietnam exiles in 1977. But I would come back to the issue in an historical context in the mid-1980s.

“Any chance of a book to follow your most interesting letter in the Times?”

When an author screams in the woods far out of earshot, does he make a sound?

I did not know what W.W. Norton was, or who Evan Thomas was, but I quickly learned that Norton was a distinguished independent publishing house, and Thomas was the son of the famous socialist of the 1930s, Norman Thomas. In his own right, Evan was a legendary NY editor who had edited William Manchester’s famous book on the JFK assassination. He quickly became my editor, and W.W. Norton published To Defend, To Destroy in the spring of 1971. As the world turns, I was hired to teach creative writing at UNC that fall, a job I held for the next ten years.

"Herndon's story in Reston's sympathetic hands cuts into the very tissue of the national debate and merits wide reading."

- Publisher's Weekly on The Amnesty of John David Herndon

I had turned passionately against the Vietnam War. Nixon came into office, promising to end the war quickly and kept it going until he was driven from office five years later, at the cost of another 20,000 American lives. Now as a veteran against the war, I gravitated to the issue of amnesty for Vietnam war resisters, no doubt because emotionally I sympathized deeply with their plight and their decision in contrast to my own course. For the next seven years, as an advocate for universal amnesty, I wrote more than any American writer about the issue. In 1970 my first magazine piece treated the Nuremburg parallel and was published in the Saturday Review. I began to debate the issue all over America, often pitted against snarling, patronizing right wing commentators. And in 1973 I published my first non-fiction book, The Amnesty of John David Herndon.

It was the story of a deserter, living in exile in Paris, who agreed to become the first test case on amnesty, by returning to America to face the music. Inevitably, the military wished to avoid a show trial and cashiered Herndon out of the service administratively and quietly. We were denied the stage we sought.

My obsession with amnesty did not end until President Jimmy Carter proclaimed a pardon for Vietnam exiles in 1977. But I would come back to the issue in an historical context in the mid-1980s.

Articles:

|

"Defecting Agents"

Appeared in the New York Times Oct 1, 1969 pg. 46 (found in ProQuest Historical Newspapers) view PDF "Is Nuremberg Coming Back to Haunt Us?" Reston's first published piece and appeared in the Saturday Review, July 13, 1970. view PDF "Vietnamize At Home" Appeared in New York Times April 10, 1971 pg. 23 (found inProQuest Historical Newspapers) view PDF "Amnesty for Arrested Foes of War" Appeared in the Chicago Tribune on Oct. 8, 1971 pg. 14 (found in Proquest Historical Newspaper) view PDF "A Proposal to the President" Oct. 9, 1971 view PDF "Universal Amnesty" Appeared in New Republic, Feb. 5, 1972 view PDF “The Case for Amnesty” Appeared in World, July 17, 1973 view PDF |

“Resisting Was Moral….”

Appeared in Newsday, 1974 view PDF "Needed: A Grand Reconciliation" Appeared in Newsday, September 3, 1974 view PDF "Limited Amnesty: Not Easy: The President Gave Himself a Difficult Job" Appeared in the New York Times Sep. 8, 1974 pg. 210 (found in ProQuest Historical Newspapers) view PDF "Real Amnesty Would be Good for America" Appeared in Newsday, March 31, 1975 view PDF "On Carter's Amnesty and Pardon Views" Appeared in the New York Times Oct. 2, 1976 pg. 25 (found in ProQuest Historical Newspapers) view PDF Statement of James Reston Jr. unpublished date unknown view PDF "Lesser Amnesties for Smaller Convulsions" unpublished date unknow view PDF; view original typed with edits |